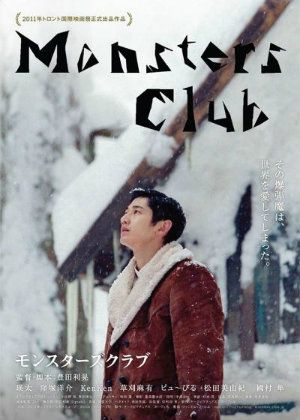

Truth be told, Monsters Club, directed by Toshiaki Toyoda and starring Japanese rising star Eita, has been a very difficult movie for me to write about. Since watching it at a preview of New York Asian Film Festival and Japan Cuts co-presentations, this piece has gone through many a false start only to halt and wait for me to come back around to it later. I’ve thought over what to include and what would best be left out, saved for when there’s occasion for a deeper discussion. Perhaps the one thing I am certain of is how hard I’ve fallen for the movie...For the strong feelings it evoked in me, and for the questions it has left me considering well after seeing it. The best approach may just be to lay out the details that comprise this unique little film and see where it takes us...

First there is the film’s potentially inflammatory premise: A story influenced by the life of infamous real life political terrorist, Ted Kaczynski (The Unabomber), about a lone individual, told with surreal elements and a sympathetic tone.

The alternate reality Unabomber depicted here is a young man inhabiting a cabin in the seclusion of Japan’s snow covered, mountainous woodlands. One thing that may give people the impression of a sense of empathy for the controversial figure is that this fictional one is far from the scraggly menace many associate with his real life counterpart of the American midwest. Rather, Ryoichi is debonair in his appearance. The details of his hermetic existence suggests a connoisseur’s appreciation of outdated relics: he listens to selections of Appalachian music and 19th century opera on a gramophone, his dwelling is carefully adorned with time worn scales, mortar and pestles, tinned powders and other antiquities. newspapers documenting corporate targets whom his homemade explosives have made their way to are not roughly strewn about, but framed, imbued with amber tones. The carefully preserved arrangement betrays the destruction these items give testimony to.

Another aspect of the film that suggests an almost appreciative look at the subject is the excerpts of Kaczynski’s manifesto (which sound as if genuine) chosen to be included and how much more poignant they perhaps are a decade or so after first being exposed to the world. Instead of emphasizing the more fanatical, violent elements, there are references to individual freedoms and basic urges, and how they are at odds with modern cityscapes, a dehumanized labor force, and the push of technology. One has to wonder if this takes on a more charged meaning, not only to a society in which the next lifestyle shaping mobile device is being marketed only moments after the current one was purchased, but in particular a young, frustrated Japanese workforce. The same that, a few years ago, were profoundly moved by the resurgence of an anti-capitalist leaning novel, Kaniko-sen (later adapted into a film by Sabu).

A simple expression of sympathy for a figure so widely regarded as a monster may seem sufficiently in character for the controversial director, who was blacklisted from Japan’s film industry after drug possession charges (only to return with the noisy, tripped out film Blood of Rebirth). However, there is much more to it than that. Behind the controversial premise of Monsters Club is a surprisingly delicate portrait of loss and madness.

After spending a bit of time in Ryoichi’s snow frosted physical environ, the story turns inward to explore the protagonist’s fragile and fragmented mental state, as he is visited by several entities. Some are ghosts of the past; others are monsters, one made up of a dripped, hardened candle wax consistency while another bears the likeness of a smeared and overly painted clown (neither would seem out of place in one of Matthew Barney’s surreal Cremaster films). The more humanlike visitors are members of Ryoichi’s family. Their living or dead status can be determined through their dialogue with Ryoichi, yet whose presence is real or imagined is a question that is trickier to answer with certainty. Flashbacks of uneasy family gatherings, tinted by a sense of over-formality and malaise, slide in and out of Ryoichi’s consciousness. This creates a clearer picture of Ryoichi’s relationship with the rest of his family, in particular, an older brother who met a tragic end. In Yuki, we find someone Ryoichi held in the highest regard, whose path seemed irreproachably pure. Yet, because of its grizzly end, Ryoichi cannot shake a sense of doubt over his devotion to it.

At its core, the film is less about manifestoes and more about the deep personal conflict that comes when one is forced to question the wisdom of that who he once revered above all others. Political agendas take a backseat to this more personal struggle to find one’s way. In this regard Monsters Club joins other contemporary Japanese films that look at directionless individuals in need of guidance. Among them, find Odagiri Jo’s twenty-something troubled soul drifting through life in Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Bright Future. Yet, while Bright Future’s stunted wanderer finds a father figure, Ryoichi has been left behind by his mentor. His salvation can only come from within.

Consider too, for a moment, the so-called ‘club’ of the movie's title. At best it is a lonely one, boasting only one living, breathing member. It may speak of a bigger societal concern in Japan. One where loneliness drives many of its youth to seek out something to share, to identify with others, even if it is an ugly, negative instinct. Look at another of this year’s Japan Cuts features that is shockingly based on true events, Let’s Make the Teacher Have a Miscarriage Club (being shown in a triptych of shorter films) to see how this desperate need for a sense of belonging can manifest itself in the most brutal of ways.

Rather than include the trailer, which in an effort to sell tickets gets the mood all wrong, here is a clip previewing a special live event, featuring director Toshiaki Toyoda and the composer of Monster Club’s score Teruyuki Terui, performing together in a live unit. While it contains few if any moments from the actual film, it features its soundtrack prominently and captures the haunting and serene melancholy that flows throughout.

Were this a dull lifeless palette, or in any way amateurish in its production, Monster Club’s mysteries might be better off left alone. It is not at all difficult to watch. In fact it is quite beautifully shot, alternating between a sleepy snow covered wilderness and the immaculately pieced together interior of Ryoichi’s cabin awash in hushed golden tones, nothing short of a minor steampunk fantasy. Then there is the soothingly mesmerizing score penned, surprisingly, by Toshiyuki Terui, member of a former J-rock band Blanky Jet City. It is made up of slow building compositions that would blend in perfectly with the likes of Bill Callahan, The Dirty Three, or the more brooding recordings of Godspeed You! Black Emperor and A Silver Mt. Zion. As the end approaches, Ryoichi’s voiceover narrative takes on a truly lyrical quality. Political contexts become intertwined with more personal ones. It is a flowing text that is not overwrought and gives the sense that it could be...even should be remembered and recited.

You need not look too hard to find ambiguities. A consideration of character’s names for instance, could give reasonable cause to call into question how much of Ryoichi’s exploits are real and how much are part of his mental perception -- the same goes for physical spaces -- are they real or a mental construct? Regardless of the interpretation one cannot negate the significance of his journey. When Ryoichi sets out into what does seem to be the world, shouldering a ticking ultimatum that demands, not the surrender of corporations, but the reading of an obscure poem, we are forced to truly reconsider his identity: Is he nihilistic radical or confused romantic?

Monsters Club is a triumph of subtle filmmaking. It poses questions whose elusive nature provokes thought rather than frustrates, and hides inner struggles inside more obvious political ones: In the end Ryoichi will succumb to pressures to carry on a malignant cycle or break free from it? This is a small, obscured marvel worth dusting off and taking a closer look at.

Monsters Club will be co-presented by The New York Asian Film Festival and Japan Cuts on Sunday, July 15 at the Japan Society.

Visit Subway Cinema and Japan Society’s guide to Japan Cuts for more information.

Me on twitter = @mondocurry

Ok, I did the research for you, what you heard at the end is actually a preexistent poem, which is made clear before in the film.

ReplyDeletehttp://masafumimatsumoto.com/miyazawa-kenji/